The Sober Thought Experiment

When the reckoning arrives, will the narrative of globalization survive?

"Those investors who limit themselves to what seems normal and reasonable in light of human history are unprepared for the age of miracle and wonder in which they now find themselves.

The twentieth century was great and terrible, and the twenty-first century promises to be far greater and more terrible."

Peter Thiel

The last decade saw a bull market like no other; in fact, the last half-century has seen more bubbles and bursts than the past combined. Peter Thiel posits that every bubble is actually a deeper story about globalism, in which a good – whether it’s tulips or internet stocks – unites the world until the market’s inevitable climax when gradually, and then suddenly, the music stops.

Rightfully so, cynicism lags behind optimism in the good times, but the second the shoe drops, they march in unison. On the tailwind of the largest bull market in history, we have to wonder what this implies for our ideas of a universal world – is this the beginning of the end for our liberal institutions or instead a second-chance to experiment with hitherto untested policies?

The signs were there if the macroeconomic investor possessed a keen and discerning eye. In 1900, before central banks obfuscated the flow of capital, the world worked in a crystal clear fashion: developed nations invested in developing nations so as to reap the returns from runaway growth. We saw this with London’s Anglo-Saxon financial centers who invested in Argentinian railroads; before that, with the European powers who scrambled for Africa; and perhaps most significantly with the first pilgrims who journeyed to America, where they would be the gatekeepers presiding over a new world: “Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moths and vermin destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moths and vermin do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal.” (Matthew 6:19).

Our era is Kafkaesque, namely because developing countries began investing heavily in the first world. The upper-middle class in China were aghast at the idea of only owning one house; in a frenzy, they were buying two or even three across continents. Certainly, this isn’t a Chinese peculiarity – it was even a staple of Russia and Saudi Arabia. This phenomenon became so common that TV shows were produced around expats spending generational fortunes in western countries like Canada.

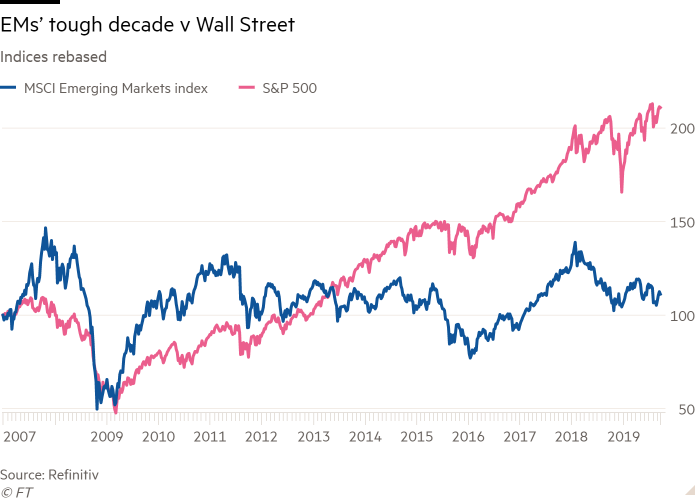

Immediately, the clamor that these investors were raising property prices ensued not just in Canada, but everywhere where oligarchs tended to mingle: London, New York, San Francisco, and Sydney. How could this be? Under the surface, the Chinese economy is the most credit-heavy in the history of the world – it puts sub-Saharan Africa to shame. The commonality between these asymmetrical levels of investment are the aggrandized amounts of capital that has flowed into emerging markets since 2000; one need not look far to see the income inequality and institutional malaise that followed.

The Decadent Society

“And as it was in the days of Noah, so shall it be also in the days of the Son of man. They did eat, they drank, they married wives, they were given in marriage, until the day that Noah entered into the ark, and the flood came, and destroyed them all.”

Luke 17:26–30

Our century has been extraordinary in many ways, but China’s fight to become the world’s largest economy is staggering. In 2000, the country controlled only 5 percent of the world’s GDP, but the fish ate the whale: it swallowed a fifth of global GDP in merely two decades. Other countries have marched in lockstep. Despite dollar-denominated debt outside the US reaching $12 Trillion, most of which is held in emerging-markets, investors are seeing the pandemic as a one-off event and a marked investment opportunity.

These investors mistakenly believe that catch-up growth is a constant: one way or another, emerging markets will nevertheless converge with the first world and they will reap biblical returns. But that view simply stands if the underlying economic order survives the coronavirus, which is appearing more like a dream than sober reality.

The geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan in his timely book, Disunited Nations, discusses the fall-out from the dissolution of the American order; what he calls the global system protecting everything from intercontinental trade to physical security, paid for by America. The United States backstopping the oceans, skies, and even digital pathways are a lingering byproduct from the Cold War where we exchanged money for loyalty against the USSR. Indeed, we don’t live in that world anymore – forthwith Americans couldn’t care less about Mongolia’s commodity prices or Russia’s income inequality – we have our own problems to consider. The days of acting as the world’s policeman are a foregone conclusion.

Yet it was this order that permitted the free flow of capital – and the successive bubbles thereafter – which precipitated the boom in emerging markets and transformed investors’ expectations ex post. But nothing can be taken for granted anymore; it’s really the war of all against all: The EU left Italy to die in the woods, leaving the IMF to clean up its bloodied carcass. However, though the IMF may possess over $1 Trillion in spending power, over half the world’s countries have asked for emergency loans already. How much longer can this continue? If the EU won’t invest in their own member-states, can we expect continued financial support, much less sympathy, for developing nations – South Africa, Angola, and Guyana?

Certainly the IMF and other Neoliberal institutions are prepared to take up the gauntlet of mediating sovereign debt crises; nonetheless, it is a mistake of the first order to overweight the past. This problem has a name: the Lucas Critique is one of the foundational puzzles in macroeconomics. In effect, Robert Lucas exclaimed that it was illogical to ponder the merits of economic policy purely based off hindsight analysis – we have no way of predicting their second-order consequences. Because economic theory is largely conjecture and is done a priori to specific policy, how confident can we be in our models? The field is more social than a science. Prudent investors who have departed from Plato’s Cave are amazed at the current “age of miracle and wonder in which they now find themselves.”

Therefore, investors who want to adapt to this new epoch must realize that it won’t resemble past styles of globalization. For this reason, we must start anew, effectively from first principles, and rethink the future of the geopolitical landscape. In this Brave New World, what does it mean to be American and what responsibilities do we carry as citizens? What are some ways the world might conceivably change this decade?

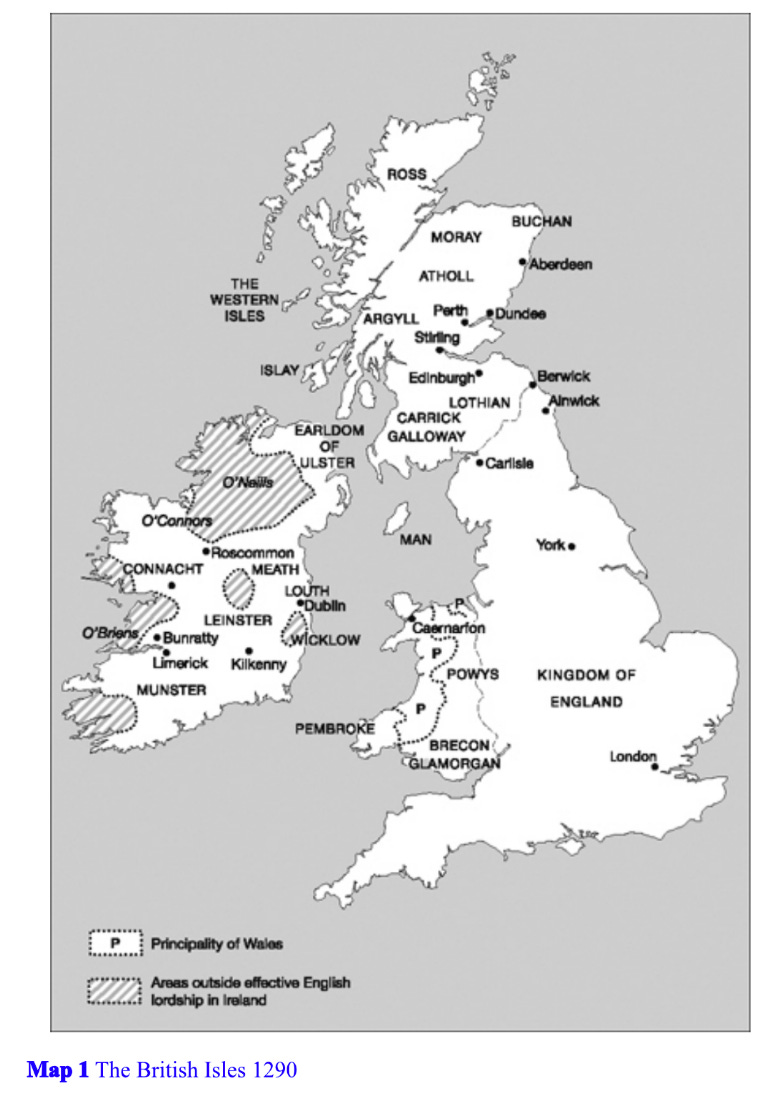

Security

As global alliances fray and new borders are drawn, security – both in the physical and cyber realms – transforms into a much more pertinent issue. Because America has been the world’s policeman, taking up the mantle from Britain, most countries have had no need to become the foremost experts in defense – this will change. Companies like Anduril are poised for the volatility due to the fact that these countries don’t have the technological expertise to catch up to Western firepower. To see the importance of security, take a look at a map of the British Isles in 1290; while I don’t think the UK (or the Kingdom of England, Scotland, and the Principality of Wales as it was then known) will break up, the rest of the world might look eerily similar to this. We took a short break from everyone being at each other’s throats and now we’re reverting to the mean.

Manufacturing

Certainly, domestic manufacturing is another area prime for development. As readers may know, I’m bullish on the semiconductor industry as a whole and even American manufacturing therewith. More significantly, Apple’s new ARM chip, due to release in the next-generation MacBook in 2021, is a sign of the times. Thus far, the chip industry has been a duopoly, but Apple is one of the few sovereign powers that can force developers onto their platform: tools shape the users and vice versa. As more engineers are shifted onto the ARM chips, the current hardware model is ripe for a shake up.

Energy & Food

At this point, It’s a stark reality that most of the world depends on network effects to some level, whether it be in the form of oil supply chains, medicine, or technology. Digging deeper, we see that the interlocked nature of economies like Brazil on some level requires the help of America. In other words, many of these countries can’t produce agriculture or appease energy demands without foreign input, all of which is held together by the American military.

But for the sake of argument, let’s suppose America wanted to hobble Brazil’s economy: we would simply have to block imports (or institute sanctions) on some of its largest imports, say pesticides for agriculture, and because of Brazil’s skill-shortage, the country is dead in the water. Taking the example of China, America need only turn off the CCP’s access to the Persian Gulf – China’s nearest source of oil reserves – and its economy would be walking wounded and declared dead in three. Why haven’t we done it yet? Therewith, the threat hasn’t been that severe; we generally used the carrot and not the stick. But as the math changed, the map changed.

Scylla or Charybdis?

“I saw New Jerusalem, that holy city, coming down from God in heaven…Nations will walk by the light of that city, and kings will bring their riches there. Its gates are always open during the day, and night never comes. The glorious treasures of nations will be brought into the city. But nothing unworthy will be allowed to enter. No one who is dirty-minded or who tells lies will be there.”

Rev 21:24

If online discourse is a proxy for Western sentiment, those who alerted the masses by proposing that the coronavirus might have surreptitiously arisen from a lab in Wuhan were considered morally reprehensible; some, like fringe financial website ZeroHedge, were even banned from Twitter. Curiously, it appears as though we must choose between the Scylla of nihilism or the Charybdis of fantastical hope.

But the reckoning will come and for those who seek the truth, the path is paved with opprobrium and violence; yet in the end, only a few will survive the flood and arise witnessing a new Earth entirely.